The installation of community microgrids powered by a combination of solar, wind, and Waste-to-Energy (WTE) electrical generation methods could lead to faster, more resilient recovery efforts throughout the island of Puerto Rico. These solutions could be specified to individual communities, creating an overall energy profile this is most effective for each region. Moreover, microgrids would allow for faster, earlier recovery and repair efforts for rural or inland communities, which would not be entirely dependent on the main grid or repairs by a central agency. The implementation of these solutions in combination with Puerto Rico’s current efforts would create a more resilient grid for future emergency situations.

While Puerto Rico has passed the Energy Public Policy Act with the goal of making energy generation throughout the island 100% renewable by 2050, that long term plan should be supplemented by traditional energy sources for short term recovery until Puerto Rico can permanently transition into a renewable energy portfolio. [1] Establishing microgrids in communities can help to ease the process of diversifying generation, as the process of implementing the microgrids allows for the creation of smaller generation plants that can be established for individual communities. Moreover, the placement and capacity for microgrids, their control centers, and their main generational plants can be specifically tailored to each community, and the most effective renewable resources can be individually evaluated. [2] Microgrids also have the added benefit of local repair. Rural or inland communities, which were the last to regain power from the main grid after Hurricane Maria, can undergo specific repairs to their own grids earlier than their connection to the main grid may be fixed.

Solar Energy Microgrids

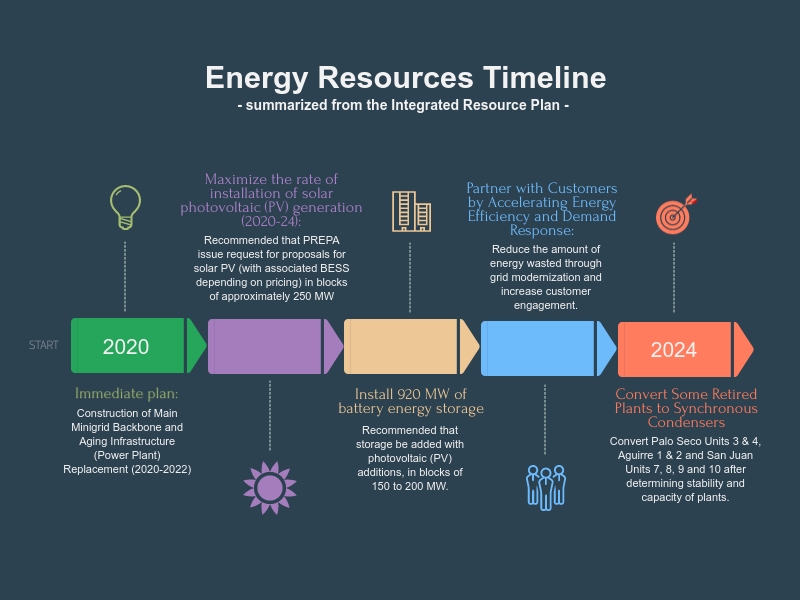

Solar energy microgrids show a lot of potential in increasing energy resilience for communities. Each neighborhood would establish its own microgrid that can disconnect from the main grid in times of storms and distress. These microgrids primarily use solar energy generation, but should still have access to traditional energy sources through connection to the main grid. According to an energy report published by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, Puerto Rico’s peak energy demand is 3,685 MW. [3] PREPA’s 2019 Integrated Resource Plan already includes adding over 2220 MW of solar energy and 1080 MW of battery storage to the main grid by 2025. [4] However, since solar-based energy generation is only effective during daylight hours, and the IRP estimates that strategically placed solar sites will produce energy with about 22% efficiency, other sources of energy must supplement solar power in order to meet all of Puerto Rico’s energy needs.

Integrated Resource Plan

PREPA’s current plan for future resiliency as outlined in the 2019 Integrated Resource Plan (IRP), prepared by Siemens Power Technology International, relies upon the installation of eight major MiniGrids throughout the island. [4] Similar to microgrids, MiniGrids are interconnected electrical grids that can disconnect from the overarching grid in times of emergency. Microgrids and MiniGrids mainly differ in size and audience, such that microgrids are for smaller ranges and are designed to remain isolated for longer periods of time. Microgrids are particularly useful for, but not limited to, rural or isolated communities and ensure that the effects of infrastructural damage can be isolated to the areas of impact, rather than spreading throughout the grid, as was seen as a result of Hurricanes Irma and Maria. Our plan for microgrids supplements the current plan for MiniGrids, and provides individual communities more electrical independence. The implementation of microgrids could greatly improve recovery efforts in future emergency situations, particularly for rural and central-Puerto Rican communities, which were typically the last to receive repairs post-Maria and were furthest from the generators for the main grid. Moreover, microgrids would allow communities to establish personalized energy portfolios based on available resources, maximizing their efficiency.

Other Alternative Sources

In addition, we propose combining an increasing dependence on solar energy with an increase in wind energy production and waste-to-energy (WTE) processes.

a.) Wind Energy: Puerto Rico has two of the largest wind farms in the Caribbean islands, [5] though only one is currently operational. The Santa Isabel Wind Farm, with an installed capacity of 95 MW, did not receive any significant damage during the storms. The Punta Lima Wind Farm, with a capacity of 24 MW, had all 13 of its turbines damaged during Hurricane Maria. Repairs to this wind farm have not yet started, but are estimated to cost about $25 million, taking approximately 9-12 months. [6] With the repair of Punta Lima and the installation of wind farms throughout the island, wind energy helps to fill in gaps, particularly during the night, where solar power is not as a consistent source. While solar power has the largest potential for efficacy on the island, as seen in Figure 2, wind power would supplement solar power to compensate for methods of energy storage that are too expensive for immediate installation.

b.) Waste-to-Energy Processes: WTE would provide multiple benefits for Puerto Rico. Puerto Rico currently has 29 active landfills, most of which are beyond capacity, and 12 of which have been closed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency due to noncompliance with environmental and public safety laws. WTE programs, which burn municipal waste (including biomass and non-biomass combustibles) are burned to generate steam to turn turbines, and have the potential to produce up to 6,800 MW for Puerto Rico. [3] While installing WTE plants and pollution control devices to mitigate gaseous toxins are costly, the EPA’s 12 recycling programs are already establishing recycling programs that can facilitate WTE. Additionally, a report from Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs estimates that while annual operation and maintenance costs would be around $30 million, annual revenue would be about $71 million, quickly paying back installation costs. [7]